TL;DR: Don’t underestimate the risks of copyright and breach of contract issues with generative AIs. Claims on either ground could be successful, and there will be lots of problems for vendors (and, maybe, end users) if they are.

Imagine it’s November 2023. The district judge in Getty Images v. Stability AI has just issued an injunction against Stability AI, prohibiting them from selling any generative AI trained with Getty Images’ copyrighted content. Potential damages look large (Getty Images has asked for over $150,000 for each of the over 12 million images that Stability AI copied), and Stability AI may have to destroy any AI trained with Getty Images content.¹ While other generative AI copyright lawsuits were already on the go, this decision drives lots more lawsuits around generative AIs trained on content without clear opt-in permission. AI image generators, code generators, and Large Language Models have gone from wowwing us to bigtime liability, all in the course of about a year.

While the previous paragraph was an imaginary scenario, this isn’t an outlandish possibility. Multiple lawsuits are already on the go against generative AI providers. They ask for penalties including injunctions, significant money damages, and destruction of AI trained using their copyright content. More lawsuits seem likely to come.

In October, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) warned that AI companies were violating copyrights en masse by using music to train their machines. “That use is unauthorised and infringes our members’ rights by making unauthorised copies of our members’ works.”

— Laura Snapes, The Guardian, “AI song featuring fake Drake and Weeknd vocals pulled from streaming services”

It seems without question that generative AI providers have ingested vast amounts of copyrighted content (e.g., web pages, images, songs, code).² Some of this content appears to have been taken despite clear website terms of use prohibiting this³. Generative AI companies claim that they have transformed this copyright content, and that their actions are an allowed “fair use.” Plaintiffs say this is a breach of their copyrights and of website terms and conditions. It seems very unclear how these suits will come out. As IP scholar Daniel Gervais says (quoting Rebecca Tushnet and David Nimmer respectively):

Predicting the outcome of a fair use case is risky business. Indeed, one well-known commentator quipped that making a fair use determination an ”unpredictable” task that “often seems naught but a fairy tale.”

Mark Lemley and Bryan Casey say:

Given the doctrinal uncertainty and the rapid development of ML technology, it is unclear whether machine copying will continue to be treated as fair use.

In the course of writing this piece, I spoke to knowledgeable people who think that fair use or the science of generative AIs is such that they won’t be found to infringe copyright. Other knowledgeable people aren’t so sure. If you’re certain generative AIs aren’t going to face copyright infringement and breach of terms of use judgements (which we’ll call “infringement” for the purposes of the rest of this post), no need to read on. If you are less than certain, you may find this piece worthwhile.

This topic is huge, and there are so many interesting pieces to be written on it. How will infringement lawsuits against generative AI providers come out? How ideally should IP work around generative AIs? Should material created by a generative AI (partially or wholly) be copyrightable? Will previously-uncontroversial web crawling and machine learning training approaches (e.g., Google training an AI to identify spammy websites) be adversely impacted by generative AI rulings? And more. In this piece, we consider what happens if Getty Images (or some other plaintiff like them) wins. That is, what happens if the law is that generative AIs can only be trained on permissioned data.⁴ We don’t know if this will end up being the case, but it seems sufficiently possible that it’s worth considering.

This piece is long - over 3,000 words. Yet our small slice of the topic is so big that we plan at least [two] more pieces covering details that interest us! We’ve added a table of contents section on the right to help speed you to parts that interest you 👉

Is OpenAI liable for writing these “Drake” lyrics? What about Uberduck, who provided the voice clone? What about Ableton, who enabled them to make the video? What about creator @GengarCade, who made the video (which is at 212,000 views as of when we write)? Is this just like a Weird Al parody or other cover, or something different? What if True Primal decided to license this tune from @GengarCade and used it to promote their beanless beef chili? What if True Primal decided to just create this work themselves, and cut @GengarCade out? So many questions!

Note that copyright rules differ by (country-level) jurisdiction. This has two implications:

- Governing bodies (e.g., congress in the US, maybe the European Commission or national governments in the EU, parliament in Canada) could act, preempting any court ruling. A form of this (stemming from privacy concerns, not preventing infringement) is already occurring: Italy (temporarily) banned ChatGPT. We’re skeptical that this is going to happen anytime soon in the US, but maybe it will elsewhere.⁵

- Different rules might apply in different jurisdictions. E.g., generative AIs might be found to be infringing in the US, and not-infringing in the UK.⁶ As we’ve seen with GDPR or California data privacy legislation, even limited-jurisdiction regulations can have a significant (restrictive) impact on tech that’s available across borders. It seems reasonably likely that different jurisdictions will treat this issue differently.

Why Might Generative AI Training Lead to Liability?

How is that different from a human lawyer reading an article from one of these sources and using it to improve her service delivery in a commercial context. Perhaps scale? Will be interesting to see which CC license was applicable.

— Amit Sharma (@capreal26) April 21, 2023

It is totally possible that courts may find that generative AI companies did nothing wrong in training their models. Or they might not. Here are two possible reasons why a court could find generative AI training or outputs violate others’ rights:

- Copyright Infringement. Many generative AIs have likely been trained on data scraped from the internet. Much of that data was likely copyrighted material - works where its owner has “the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform [the] work, usually for a limited time” (e.g., 50, 70, or 100 years after the death of the author). This Washington Post article (using a different, but they think comparable, dataset to that used by some generative AI vendors)⁷ suggests that “The copyright symbol — which denotes a work registered as intellectual property — appears more than 200 million times in the C4 data set.” Maaaaaaaaybe generative AI companies (1) got permission for some of these or (2) use a materially different data set, but both seem unlikely. Both the vast amount of training data and the way generative AIs are built mean that generative AIs may be unlikely to spit out content identical to what they were trained on. However, their inputs are problematic and the outputs can (1) be similar in form and (2) imperil the livelihood of the original authors whose work was trained on without consent. There are counterarguments, and it’s TBD how courts will see this.

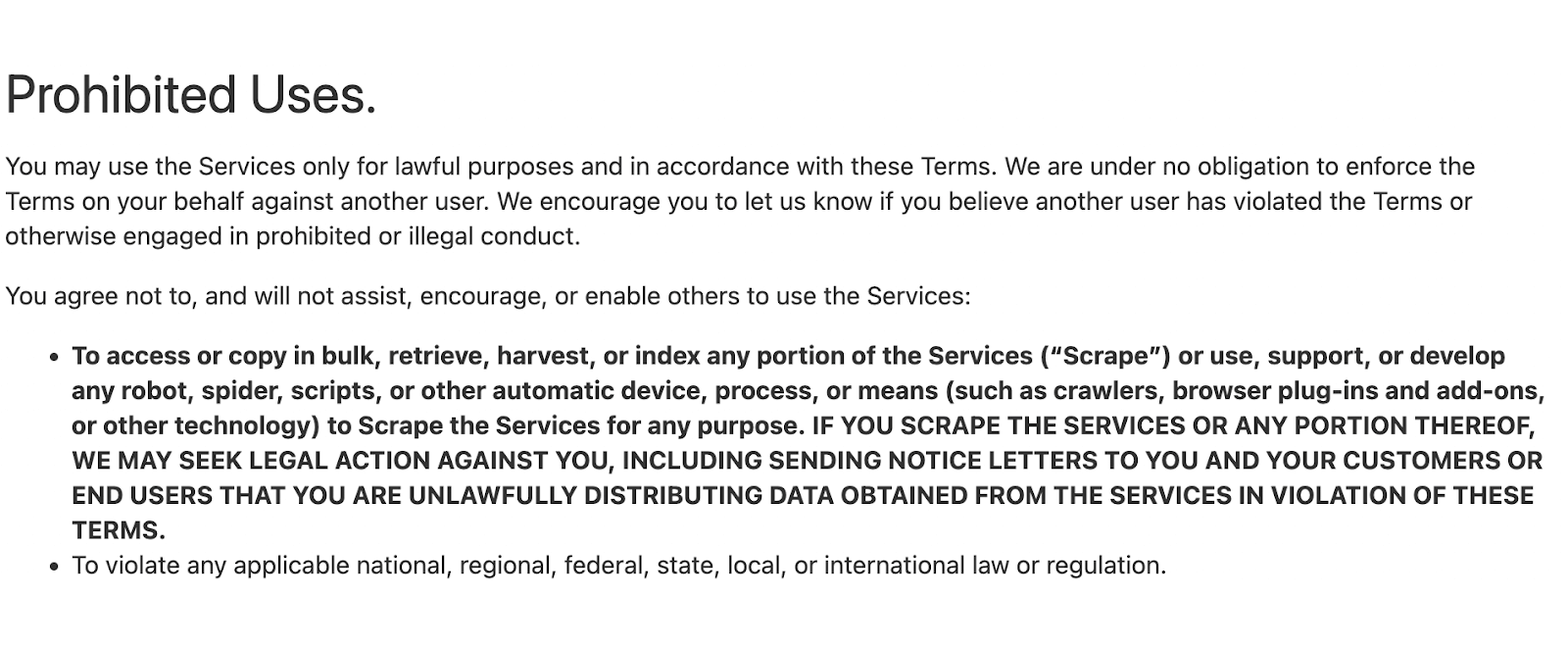

- Breach of Contract. Many websites have terms of service (a.k.a., terms of use). These set the terms between a website and its users. Some set what users can do on the website, and prohibit things like scraping or using content for a competitive purpose.⁸ Here’s an excerpt from the Law Insider Terms of Service (last updated 1 September 2021; Law Insider may have been among the top legal websites providing training data for Large Language Models like GPT):

In the US, while web scraping has been ruled to not violate laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, scraping in contravention of terms of use has been found to be a breach of contract.⁹ ¹⁰

In the US, while web scraping has been ruled to not violate laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, scraping in contravention of terms of use has been found to be a breach of contract.⁹ ¹⁰

As with our copyright infringement discussion above, it’s possible that generative AI companies only trained on data where website terms of use didn’t restrict them from doing so. This seems low probability.

As people who care a lot about knowing the details of masses of contracts, we plan to write more on this topic.

A court could find generative AIs problematic under either (i) copyright infringement or (ii) breach of contract; Also, suits only need to be successful in one major jurisdiction for there to be real issues. The combination of these make us think that it’s reasonably likely that generative AIs are found to infringe.¹¹ But this is TBD, and maybe generative AIs will come through unscathed.

What Happens To Companies That Build And Sell Generative AIs If Their AIs Are Found To Infringe?

Most likely, infringing generative AI builders would have BIG problems.

On copyright claims, the worst case scenario is class action lawsuits with the claimants being everyone who had their material trained on without permission, and willful infringement statutory damages for all registered works copied. Damages are probably worse for copyright infringement than they are for breach of website terms of service. Statutory damages in US copyright cases range from ≥$200 for each work innocently infringed up to as much as $150,000 for each work willfully infringed.¹² Hundreds of millions (or more?) of works may have been infringed, depending on how a court counts.

On breach of website terms of use, it’s hard to estimate damages. As with copyright claims, the scope of the infringement is vast, which means damages could add up.

The real killer in both copyright and breach of contract situations might be injunctive relief - preventing the use or sale of an AI trained on infringing content perhaps only temporarily, e.g., while a court more fully considers the issues. AI providers would likely have to retrain their AI on non-infringing (opt-in or otherwise permissioned) data. This raises interesting issues: what would it take to exclude offending content from the training data? Would the generative AI vendor have to retrain fully? It is hard for us to be sure of the answer. It would somewhat depend on how the generative AI was trained. Assuming the training data was linearly organized (e.g., train on all stuff from website X, then website Y then website Z) then it’s possible the vendor could go back to a checkpoint before that data and retrain from there without it. We think it’s more than likely it would basically be a full retrain. This is unideal, since generative AIs tend to be very expensive and time consuming to train.

While several pure-play generative AI startups have raised big funding rounds at high valuations, the really interesting risks here are to big tech companies (e.g., Microsoft, Google) that have gotten heavily into generative AI. This may work out very well for them, or not. We’ll see.

How Well Do Generative AIs Work If Only Trained On Permissioned Data?

Among a bunch of other remedy requests, Getty Images has asked that the court

[Order] the destruction of all versions of Stable Diffusion trained using Getty Images’ content without permission;

If generative AIs are forced to retrain on non-copyright content, how well might we expect them to perform? On the positive side, permissioned-data AIs should be quicker and cheaper to train (because they are trained on so much less content)¹³. On the negative side, they probably won’t have the broad capabilities we see from current generative AIs (though may perform well in narrow domains, if sufficient non-infringing material can be found to train them).

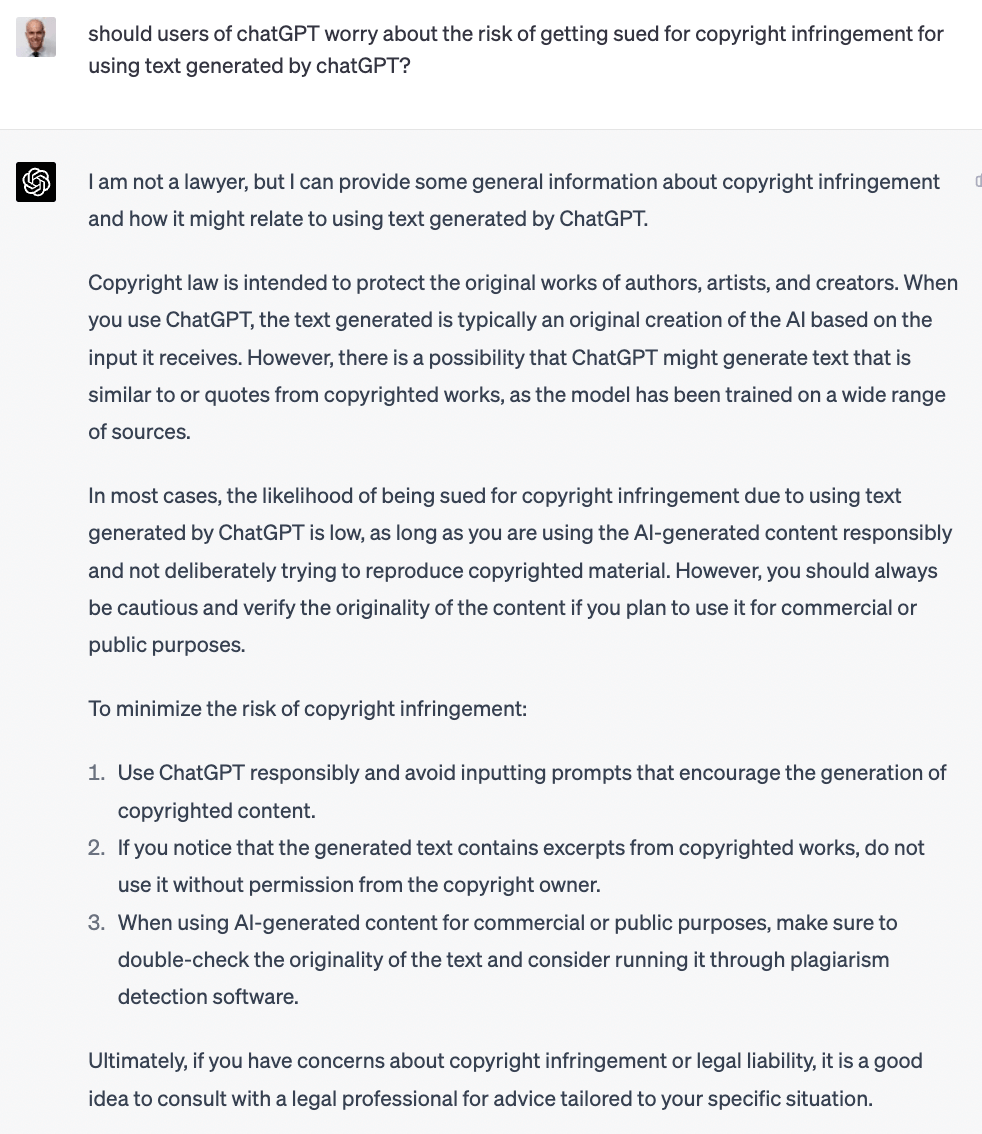

Do Downstream Users Of Infringing Tech Face Infringement Liability?

We’re more concerned about risk here than GPT-4 seems to be (at least with the response to this sp/cific prompt).

Most of us don’t run generative AI vendors. We’re users, starting to incorporate the tech in our work, either directly (e.g., via ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, or the OpenAI or Anthropic APIs) or indirectly via apps built on top generative AIs (Jasper, GitHub Copilot, Casetext CoCounsel, some forthcoming Zuva features 😁, many more). If generative AIs are found infringing, is there any way an end user of an infringing generative AI could face liability? It’s hard to say. Some cases seem more clear cut: using generative AIs to produce close copies of copyrighted material is probably a bad idea. E.g., doing “Drake” mashups is risky business.ⁱ⁴ Beyond that (and generated code, which we’ll cover below), it’s too early for us to tell whether there could be liability and how costly claims might be.

It seems possible that there could be downstream liability. Though different in important ways, we are reminded of patent lawsuits against users of scanners, back around a decade ago. In the end, the scan-to-email patent troll had their patent invalidated, but caused a lot of angst along the way.

Our best guess is that if there is downstream liability (outside of fraught areas like (1) content that intentionally copies the style of another or (2) generated code), penalties are likely to be less severe while there is more legal uncertainty. That is, current end users are less likely to be punished severely for their actions. As legal certainty grows, expectations of proper behavior will too. Of course, if generative AIs are found to infringe, they will probably become much harder to access, making it less likely that end users will do something that would make them liable.

Generated Code May Have Extra Problems

Generated code may be risky in a distinct way from generated images, sounds, or text. Some generative AIs have been partially trained on open source code. Open source code is subject to license agreements with very specific terms. There are multiple different open source software licenses, and the details of them really matter. Among other critical details, some licenses do not permit commercial use, and others (e.g., the famous GPL) require that all software that incorporates elements of the licensed code themselves be licensed under equivalent “copyleft” terms. Accordingly, commercial software vendors tend to be very careful about what open source code they incorporate into their products.

A court might find that downstream uses of code generating AIs yield code subject to licenses that the generative AIs were trained on.ⁱ⁵ While we have seen vigorous debate on this issue, we are uncertain how it will come out. Worst case, users of generative AI code generation platforms could find software they built subject to license restrictions carried through from software the generative AI they used was trained on. This could apply retrospectively. For commercial software developers, that could be a disaster - potentially open sourcing their closed code. No idea if this will happen, though it would be a bad outcome for some if it did.

What Might Happen Under Generative AI User Agreements If The Tech Is Found To Infringe?

In software contracts, it’s pretty typical for there to be language describing what happens if the vendor’s tech infringes. Usually, vendors have replacement and refund obligations and options, and vendors indemnify customers against claims that the vendor’s software infringes someone else’s IP. We thought it would be interesting to examine what (1) generative AI builders, and (2) applications that publicly claim to heavily incorporate generative AI offer in the way of indemnification, especially for IP infringement. This matters because if generative AIs are found to infringe, end users may find their software doesn’t work fully, and they are (maybe!) on the hook for damages. So generative AI customers should know what will happen if vendors infringe. Of course, the potential damages here might be so large that vendors could be unable to make good on their indemnification obligations.

In typical Zuva-blog fashion, delving into the details here turned out to be a big question in and of itself. Meaning this already-long post would be even longer. Rather than that, we’ve carved this out into a separate post, which should drop soon.

What End Users Can Do To Mitigate Risks Of Generative AI Infringement Claims

As end users of generative AIs, if you’re worried, there are things you can do short of not using the (pretty amazing) tech. A few stand out to us:

- Eyes wide open. Make sure you pay attention to how courts in relevant jurisdictions are treating generative AIs. Our guess is that if end users face material liability, it is more likely to occur on use after courts have found generative AIs infringing.

- Use generative AIs trained on permissioned documents. There are currently limited options here (e.g., Adobe Firefly, or for code, models trained only on data like The Stackⁱ⁶), but maybe more will come if courts restrict non-permissioned training. If you’re very worried about risk here, these could be an option.

- Use a generative AI not generating new text. Maybe, maybe courts will hold that more transformative uses are valid.¹⁷ If so, then it may be okay to use generative AIs in ways that their outputs are tightly constrained. E.g., have the AI choose from a set list of outputs. Either way, we think this approach could be very useful in the contract analysis space, and will write more on it soon.

- Be especially careful using generative AIs to write code. There is a real risk that your generated code may be subject to restrictive copyleft terms.

- Don’t mess with Drake. Recognize that if you create content using generative AIs that closely matches an artist’s style, they may come after you.

- Check your vendors. For your vendors who have incorporated generative AI, it’s probably worth figuring out (a) whether the vendor indemnifies you against IP infringement claims, (b) if they will replace or refund in case of infringement, and (c) if they are conscious of risk here. We have a forthcoming piece on (a) and (b) that should drop soon.

- Consult your counsel. You should talk to your lawyers if you’re at all worried about this. Note that we’re not your lawyer, and this piece isn’t legal advice.

It will be super interesting to see how this all comes out!

Further Reading

Fair Learning, Mark A. Lemley and Bryan Casey, Texas Law Review.

A Social Utility Conception of Fair Use, Daniel Gervais, Vanderbilt Law Research Paper No. 22-35, March 15, 2023.

Getty Images v. Stability AI Complaint, February 3, 2023.

Stable Diffusion litigation law firm website, Joseph Saveri Law Firm.

Generative AI Has an Intellectual Property Problem, Gil Appel, Juliana Neelbauer, and David A. Schweidel, Harvard Business Review, April 7, 2023.

The scary truth about AI copyright is nobody knows what will happen next, James Vincent, The Verge, November 15, 2022.

AI art tools Stable Diffusion and Midjourney targeted with copyright lawsuit, James Vincent, The Verge, January 16, 2023.

Getty Images is suing the creators of AI art tool Stable Diffusion for scraping its content, James Vincent, The Verge, January 17, 2023.

Getty sues Stability AI for copying 12M photos and imitating famous watermark, Ashley Belanger, Ars Technica, February 6, 2023.

An Insurer Sent Law Firms a ChatGPT Warning. It Likely Won’t Be the Last, Isha Marathe, Legaltech News, April 13, 2023,

An AI Hit of Fake ‘Drake’ and ‘The Weeknd’ Rattles the Music World, Joe Coscarelli, The New York Times, April 19, 2023.

Inside the secret list of websites that make AI like ChatGPT sound smart, Kevin Schaul, Szu Yu Chen and Nitasha Tiku, The Washington Post, April 19, 2023

Thanks

Big thanks to Lorie Waisberg, Dr. Alexander Hudek, Charan Sandhu, Benedict O’Halloran, Maya Lash, Steve Obenski, and Kennan Samman for discussing ideas and (in some cases) reviewing a draft version of this piece. All mistakes are ours.

1. Note that Noah was a lawyer at Weil Gotshal (Getty Images’ law firm in this lawsuit) earlier in his career. He also spoke to a current Weil lawyer (among other people) in preparing this piece. He doesn’t think his connections to Weil biased him in writing this piece (other than to think that they are a high quality law firm), but you might.

2. In the Stability AI situation, Getty Images found evidence that Stability AI pulled from Getty Images content. Other generative AI vendors, like OpenAI, have been tight-lipped about their sources of training data. This seems unlikely to help them much if they get sued. Plaintiffs will demand discovery, and OpenAI personnel will likely have to testify as to sources of training data and provide other information. Imagine trying to obfuscate sources of training data (or just not know) with someone like this plaintiff’s lawyer (Joe Jamail, now deceased, made well over $1billion as a high-end plaintiff’s attorney) on the other side! Note also that the EU looks likely to require that generative AI builders disclose copyright material used in training their systems.

3. See, e.g., the Getty Images complaint and below. We plan to write more on terms of use.

4. We say “the law” here, because this could come through court ruling or affirmative government action (like legislation or administrative action).

5. A governing body could be a legislature or an administrative body. If the European Commission acts, we are unsure who they would favor: (1) big US tech companies who trained their AI by scraping the internet for data they didn’t have permission to use, or (2) artists 😆

6. Note that Getty Images has sued Stability AI in both Delaware and London.

7. To look inside this black box, we analyzed Google’s C4 data set, a massive snapshot of the contents of 15 million websites that have been used to instruct some high-profile English-language AIs, called large language models, including Google’s T5 and Facebook’s LLaMA. (OpenAI does not disclose what datasets it uses to train the models backing its popular chatbot, ChatGPT)

8. Interesting question we don’t know the answer to, but may learn about as lawsuits play out: what if a site’s robots.txt instructions and their terms of use are inconsistent with each other?

9. Note that while we went through multiple case descriptions and a couple pages Google results, we did not do comprehensive legal research on this point, and there could be more case law on the (interesting!) issue of scraping in contravention of website terms of use (especially when the terms of use are in browsewrap (as opposed to clickwrap, where stronger affirmative consent occurs) form.

10. Scraping is core to a lot that happens on the internet today. A ruling on these issues may inadvertently impact stuff we today think is non-problematic. make us think that it’s reasonably likely that generative AIs are found to infringe.

11. Say you think it’s pretty unlikely that a court finds that generative AIs infringe - giving generative AI defendants an 80% chance of winning on each of the copyright infringement and breach of contract claims. And say we only consider three jurisdictions: US, EU, and “other” (UK, Canada, many more). Assuming one case has two counts (very loosely anyways, copyright infringement and breach), finding in favor of the defendant has 0.8*0.8 chance of success (=0.64). If the defendant is taken to court three times each with two counts (equally likely of winning) then it’s 0.26. Of course, this is a lot more complicated. Note that: 1) Things may not work monolithically in the EU. This could go country-by-country. 2) The US could offer inconsistent judgements across circuits and states, at least until a Supreme Court ruling. Breach of contract could happen under state law and not necessarily be impacted by a Supreme Court ruling. 3) Case results may not be independent across jurisdictions. While precedent only binds courts in a hierarchical relationship, courts often look to how courts in other jurisdictions have ruled as a persuasive factor to consider. Overall, only one suit needs to be successful in one major jurisdiction for the ramifications to be felt the world over, greatly reducing the chances that generative AIs remain unscathed.

12. Many pieces of content are copyright protected, but less are registered (which requires a formal filing, and so tends to be more often done for more professionally-published works). For statutory damages to apply, the copyrighted work needs to have been registered. Still, real damages can occur on non-registered work.

13. We note that Stability AI is launching an “opt-out” for copyright holders to pull their content from the Stability AI training set, and other generative AI builders may do the same. We’re skeptical that opt-out will be enough to avoid liability here, but it could be. In the EU, we think opt-out is especially unlikely. Given how GDPR and AI regulations are turning out, opt-in appears to be the default, not opt-out. Also, opt-out would require notification that is not feasible at web-scale data scraping.

14. Interesting question: should generative AI builders face extra liability if their users use the tech for improper purposes?We’re not sure. In ways, this is somewhat reminiscent of the “Betamax case,” where manufacturers of VCRs were not liable for their users’ use. However, if courts hold that it’s acceptable to train on Drake songs but the provider doesn’t make it hard/impossible to produce Drake clones, then we could imagine liability on the provider.

15. If a court found that licenses from the trained-on software should apply, it would be hard to figure out which specific licenses should apply.

16. Besides offering a dataset of permissively-licensed source code, The Stack also offers an opt-out option, so developers can choose to have their data excluded from the dataset.

17. This would likely require a degree of nuance that seems unlikely in initial rulings. Essentially, it requires there to be standards for ’training on non-permissioned data when the end use of that data fits X criteria.’ Is it possible we get there? Sure. Do we think it’s likely to come in the first pass? No.